Is the UN avoiding the inevitable legal regulation of cannabis?

Text by Aleksi Hupli, Ph.D. candidate, University of Tampere Finland

Cracks in the “Vienna Consensus” continue

What kind of form the inevitable legal regulation of cannabis will take on, remains an open question. As we enter into another decade of cannabis policy, what is called for are well-thought out policy and regulation guidelines that give priority to communities already involved in the cultivation of cannabis, industry standards that protect consumers but are not impossible to meet without large investments and a more humane approach to drug policy in general.

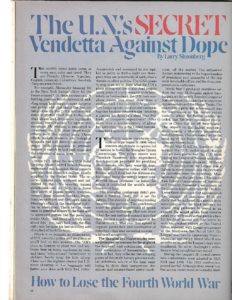

A High Times magazine article from 1976 featured an article by Larry Simonberg titled: “The UN´s Secret Vendetta Against Dope”. In the article, Simonberg writes: “One current U.N. publication lumps opium, cocaine, and cannabis together because innocents can ´develop a craving for them in a short time that leads to complete dependence´. After more than a quarter-century of global fact-gathering, this is the United Nations´ considered opinion of marijuana.”

One would wish that in 2019, almost half a century after Simonberg wrote his article, the UN´s “considered opinion of marijuana” would have been brought to the 21st century. It hasn´t, but we are getting closer. The Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) gathered in Vienna for the 62nd time after a special Ministerial Segment was held the previous week (14-22nd of March 2019). The special Ministerial Segment was due to the fact that the 2009 Political Declaration and Action Plan on Drugs came to the end of its 10- year term.

The 2019 political resolution that followed failed yet again to recognize the impossibility of the “drug-free world” goal set in place already in 1998. According to a statement by the International Drug Policy Consortium “the ‘Vienna consensus’ stifles progress on UN drug policy”:

“While we acknowledge that the statement represents limited progress in some areas, we regret that it repeats the mistakes of the past and was negotiated in the absence of a genuine and honest evaluation of the past decade, since the adoption of the 2009 Political Declaration and Action Plan on Drugs.”

The 62nd CND also decided to postpone the vote on the recent recommendation of the World Health Organisation to reschedule cannabis and cannabis resin from Schedule IV (most restrictive schedule, with no recognized medical use), to a less restrictive schedule. While disappointing, this was hardly a surprise, as the decision to postpone was one of the items on the Commission agenda already before the meeting.

The postponing of the vote was criticized by Uruguay, the first country in the world to legally regulate non-medical use of cannabis, and Mexico, while welcomed by countries like Russia, Chile, Nigeria, and the USA. The representative from Uruguay said that:

“The Delegation of Uruguay has stated that we do not agree with the fact of postponing the necessary discussion on the recommendation of the World Health Organization regarding the reclassification of cannabis, given the growing scientific evidence indicating that this substance could be beneficial for treat different health problems.”

At the time of writing, it is still unclear whether the vote will take place later this year at the reconvened session of the CND, or in 2020 at the 63rd CND as suggested by the USA (or postponed even further).

What are the practical implications of rescheduling cannabis to a less restrictive schedule, and also, are we ready for it?

But let´s pretend for a while that the CND had voted on the recommendation, and let´s imagine that the vote would have followed logically the other recommendations that the WHO presented at the 62nd CND, which were unanimously accepted by the member states. Imagine waking up to a news headline “United Nations ends decades-long prohibition of cannabis”. What would that mean? In other words, what are the practical implications of rescheduling cannabis to a less restrictive schedule, and also, are we ready for it?

Firstly, it would recognize the medicinal properties of cannabis in the international scheduling system, something that a growing number of Member States have already implemented in their legislation in various ways, but which is still lacking in the majority of countries.

Secondly, it would open up research, as discussed in a side-event titled “Science in context: freedom of research with scheduled substances” organised by Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), The International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research & Service (ICEERS), Science for Democracy and Associazione Lucacoscioni, although disputed by the representative of the Russian Federation who stated that the current scheduling has not prevented countries to conduct research:

“In recent years, the medical cannabis market has developed substantially. The presence of cannabis in Schedule IV doesn’t stand in the way at all.”

Thirdly, it would very likely boost interest of national and international companies to invest in the increasingly regulated and legal (medical) cannabis market. And while this is already happening, for instance in Colombia, there is a need for national and international ethical guidelines to ensure that those who have been negatively affected by the “war on cannabis”, are not left out when the regulated legal cannabis market expands.

There were three such guidelines published during the 62nd CND. First one by the Foundation for Alternative Approaches to Addiction – think & do tank (FAAAT) on the last day of the Ministerial Segment titled: “Cannabis & Sustainable Development. Paving the way for the next decade in Cannabis and hemp policy”. The second one was published on the 21st of March at a side-event at the CND organised by the Government of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Transnational Institute (TNI) and Intercambios Puerto Rico titled “The CARICOM Marijuana Commission & fair trade options for the cannabis market”.

Additionally, the director of TNI Drugs & Democracy programme Martin Jelsma and David Bewley-Taylor director of the Global Drug Policy Observatory (GDPO), published earlier in March a report titled “Fair(er) Trade Options for the Cannabis Market”. In the report, they argue “that policy-makers at a range of governance levels should grasp the opportunities afforded by the dramatic shifts in the cannabis market to help shape its growth and to ensure that it will enable cannabis producers in the Global South to transition out of illegality.”

In a similar way, the publication by FAAAT draws broad, yet detailed suggestions to link cannabis and hemp policies in line with the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG´s), the 2016 UNGASS Document and international Human Rights standards. The CARICOM publication, on the other hand, is more focused on regional aspects and country-specific context. Both types of approaches are argued to be important when moving from prohibition to market-regulation of cannabis.

As shown in the case of Colombia, the opening of the legal market invites actors who are mainly concerned about profit-making and keeping stock-holders happy. These actors are reaping the fruits of labor from farmers, activists, researchers and other representatives of the “cannabis movement” that have fought for decades to correct the errors of prohibition. This is something that authors of the reports are also warning about, exemplified here by the Prime Minister of Jamaica in his speech that was presented at the publication of the CARICOM report. In addition, in a video interview by Drugreporter with Michael Krawitz from FAAAT, Martin Jelsma from TNI and Lisa Sanchez from México Unido Contra la Delincuencia (MUCD), the discussants see a form of pharmaceuticalization of medical cannabis happening on one hand, and corporate take-over of the cannabis reform movement on the other. For instance, Martin Jelsma stated that: “I do think it should be one of our next big challenges, to counter this corporate capture which is going on, both in the medical and in the non-medical licit cannabis markets.”

This ultimately favors Big Pharma and Big Business type of actors who have the resources to conduct the studies required for medical products, despite the fact that cannabis is not an easy fit to the current model of “monomolecular” medicine. The publication by FAAAT also states that “Policies should ensure legal international trade benefits the populations that have been growing Cannabis for generations” (Riboulet-Zemouli et al 2019, p. 11).

But is it possible to avoid corporate take-over of cannabis?

Does big business already have everything in place that when legal restrictions are lifted, they are able to move in and simply replace the existing market that has so far been forced to work in the shadows? Is it possible to bring the ethics of the cannabis movement, based on principles of social responsibility, to the capitalistic framework of propriety rights and profit maximization? We need to begin answering these questions, and the publications mentioned above provide a good place to start.

Another relevant publication that was released during the CND was the International Guidelines on Human Rights and Drug Policy. Combined with the statement made by the executives of all UN institutions, including the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC), supporting decriminalization of personal use and possession of drugs, I would argue that this marks a historical shift in international drug policy towards more public health perspectives. Of course, there´s a long way to go to end the War on Drugs. As disappointing as it is that the “drug-free world” -rhetoric remains at the forefront of many Member States drug policy formation, it is encouraging to note that civil society engagement, especially by a new generation of youth activists, is also gaining ground together with harm reduction practices and human rights discourses.

At the same time, the distance between countries ready to reform and those who wish to hold on to the status quo seem to be growing. As Drugreporter states “what we see is a polarisation of opinions rather than linear progress”. But progress is happening, although slower than many would hope. As stated in the introduction of Cannabis & Sustainable Development “The reformist trends in Cannabis policy globally is an ongoing movement unlikely to be stopped.” And while this is hopefully true, the authors also emphasize that “Ethics are needed” (Riboulet-Zemouli et al 2019, p.5).

Part of the ethics is the transparency of the UN decision-making process. Mainstream media was hardly, if at all, present at the 62nd CND or the Ministerial Segment, despite the high profile and global impact of the meetings. However, modern information technologies allow civil society and other participants to get the information out in the public, by tweeting, live streaming, video-recording and real time blogging.

So the “UN´s Secret Vendetta against dope”, as Simonberg put it in his High Times article, is not so secret anymore.

Thanks to Amy King from FAAAT for showing me the High Times magazine article.

Riboulet-Zemouli K., Anderfuhren-Biget S., Díaz, Velásquez M. and Krawitz M (2019) Cannabis & Sustainable: Paving the way for the next decade in Cannabis and hemp policies. FAAAT think & do tank, Vienna, March 2019. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available here.